Japanese onomatopoeia is a fascinating and incredibly varied part of the language. In fact, it’s so varied that there’s at least five different types of onomatopoeia, some which we don’t even really have an equivalent for in English!

In this article, I’m going to give you an overview of what Japanese onomatopoeia is, as well as give you a ton of interesting words to try out yourself! So…

What is Japanese onomatopoeia?

Japanese onomatopoeia are more accurately ideophones, since they include actual sound representations (barking = wan-wan) as well as “sound-symbolic” words for things that don’t make sounds (e.g. damp = jime-jime; lazing around = goro-goro).

What’s this about ideophones?

So, to avoid the ire of all the linguistic pedants out there, I’ll try to clarify some nit-picky details.

Japanese “sound-symbolism” can be broken down into at least five different categories. When casually discussing the Japanese language, we usually refer to all of these types of words as “onomatopoeia” in English. However, this is technically incorrect.

Onomatopoeia are words that imitate sounds. In English, these are words like “woof,” “ah-choo,” and “tick-tock.”

Ideophones are words that that create an impression of an idea through sound. English has relatively few of these. Some of these rare examples would be “zig-zag,” “twinkle,” “helter-skelter,” and “zoom.”

Japanese, on the other hand, has tons of both onomatopoeia and ideophones. In fact, it has multiple different categories of ideophones!

Is there a Japanese umbrella word for onomatopoeia/ideophones?

As far as I can tell, there’s no “official” word that encompasses all the different types of sound-symbolism in Japanese, but the most commonly used one seems to be giseigo (擬声語 | ぎせいご).

Giseigo is made up of three kanji. The first is 擬 (“gi”), which means to mimic or imitate. Next is 声 (“sei”), which means voice. And the last is 語 (“go”), which means word or language. So, we get “imitate-voice-word.” Makes sense!

While, we’ll be using “giseigo” for the rest of this article, I thought I’d mention some other words used to describe the same concept:

擬声法

gi-sei-ho

“imitate-voice-principle”

声喩

koe-tatoe

“voice-metaphor”

声喩法

koe-tatoe-ho

“voice-metaphor-principle”

物声模倣

monokoe-moho

“true-voice-imitation”

写音法

sha-on-ho

“copy-sound-principle”

オノマトペ

onomatope

From the French “onomatopée,” which we get onomatopoeia from in English as well.

What are the different types of onomatopoeia/ideophones/giseigo?

There are at least five different categories, as well as two more aspects I’d like to discuss. Let’s go through them one by one.

擬声語

giseigo

While this is used as a catchall term, it is also the word used to describe a specific type of Japanese sound-symbolism. This one would be denoted by the technical term, “animate phonomime.”

That is to say, this is the term for words that mimic sounds made by living things.

This makes sense when we look at the kanji. That center character 声 means “voice,” in effect, the intentional sound made by something living.

Examples in English would be “woof,” “meow,” etc.

擬音語

giongo

This is what we’d call an “inanimate phonomime.” Again, this makes sense when we look at the center character 音, which just means “sound.” We use giongo to describe sounds made by inanimate things.

Examples in English would be “plop,” “pitter-patter,” “bang,” etc.

擬態語

gitaigo

This is what we’d call a “phenomime,” and it’s used for a type of sound-symbolism we don’t really have in English. Gitaigo are used to describe phenomena—concepts like “damp,” “stealthy,” “the warmth of food.”

That center character is 態, meaning condition, appearance, or appearance. See? Makes sense again!

擬情語

gijogo

This is a “psychomime,” and it’s used to describe feelings and emotions. Again, we don’t really have this in English. In Japanese, you can describe irritation, joy, and hunger, all through these gijogo.

Let’s take a look at that center kanji. 情 means, simply, feelings and emotions.

擬容語

giyogo

This one doesn’t have a fancy technical name, and I’m not 100% sure it’s even an official term. Still, it’s referenced a few times in both English and Japanese sources, so we’ll roll with it.

Giyogo is the term to describe movement. Ideas like “sluggishly,” “rattling,” “aimlessly,” etc. The center kanji in this one 容 means “form.”

Dividing up the giseigo

There’s a couple of things to keep in mind here. First is that a word can be used in different senses. For example, let’s take ゴロゴロ (goro-goro).

In once sense, it is a giongo, describing the sound of thunder.

In another sense, it is gitaigo, describing the state of loafing around.

Another thing to note is that giseigo come in a handful of forms.

The first, and most instantly recognizable, is the double form. Goro-goro, doki-doki, waku-waku. These are usually used as adjectives, though sometimes as verbs, or adverbs.

The next is those that end abruptly, indicated by a small-tsu (っ). These are also usually followed by と (“to”), indicating that it is a quotation of sorts.

Then we have the words ending in り (“ri”). These are typically adverbs and are usually in words that indicate softness or slowness.

Words that end in ん (“n”) typically denote a continuous, repetitious action or state.

Words that end with a loooooong vowel indicate something continuing for a long time.

And, of course, it’s worth noting that these are, as Captain Barbossa would say, “Guidelines.” Japanese, like English, is filled with exception and counter-intuitive twists.

So, let these points guide you, but don’t take them as hard and fast rules.

Interjections

At least one resource I delved into wrapped interjections into the overall discussion of onomatopoeia and Japanese. These are, in a sense, natural human cries that are an explosive mimesis of a psychological state.

In English, we recognize these as “Oh!”, “Ow!” Aww!” and the like.

Since this is not a main part of Japanese sound-symbolism, I won’t go into depth about it here. I just wanted to make you aware of it, and give a few examples.

あや

aya

“Wow! Whoa!”

Used as an exclamation of wonder.

いや

iya

“Oh! Why!”

“Quit it!”

Usually an exclamation of unpleasant surprise.

おやおや

oya-oya

“Oh my! Oh dear! Oh my goodness!”

Commonly used by women to express mild surprise.

おい

oi

“Oi! Hey!”

This one is pretty similar to “oi” in English, actually.

へえええぇぇぇぇ

heeeeeeeeee

“No way? Seriously? Wow! Cool!”

A huge catchall expression that you will hear all.the.freakin’.time. if you go to Japan or watch live Japanese television.

The suggestions of sounds

Another related idea is the way that sounds in Japanese suggest different ideas. As you go forward into the world of Japanese as well as sound-symbolism, you’ll be able to suss out some things just by the sound of it. Let’s go through a few of them.

The nasal “n” sound, in Japanese, suggests something subjective, or speaker-oriented. To illustrate this, we’ll use the synonyms “kara” and “node.”

Both of these mean “because,” however “node” will be used to suggest an explanation that is more personal.

Next, we have the distinction between voiced and unvoiced consonants in our giseigo. Unvoiced consonants tend to represent the small and delicate, while voiced consonants suggest big, heavy things.

For example, if you were to cut a thin piece of paper, you might use “saku-saku” to express that; on the other hand, if you were slicing up cardboard, you’d say “zaku-zaku.”

Notice how “sa” doesn’t require you to vibrate your vocal cords to pronounce properly, while “za” does. Another example of this is something small rolling, which is “koro-koro,” while something big rolling is “goro-goro.”

That distinction between what requires the vocal cords and what doesn’t is the difference between voiced and unvoiced.

Next, there’s the consonants k and g, both of which suggest things sharp, hard, or sudden (Kachi-kachi > frozen stiff).

“S” sounds suggest quiet things (shin > silent).

“R” sounds suggest smooth fluidity, even slipperiness (nuru-nuru > slimy).

“M” and “n” sounds suggest warmth and softness (mochi-mochi > springy, doughy).

“P” sounds suggest strength, explosiveness, and crispness (pisahri > splat).

“Y” sounds suggest softness, weakness, and slowness (yukkuri > slowly).

“U” sounds suggest human-oriented situations (utsura-utsura > drowsily).

“O” sounds suggest human-oriented things as well, but usually negative (oro-oro > flustered, bewildered).

“E” sounds suggest off-color things, or unpleasant things (hebereke > dead drunk).

Wait, do you actually expect me to use these words?

Absolutely. If you want to sound fluent, anyway.

To a lot of people who don’t speak Japanese natively, the copious use of these sing-songy sound-symbolisms can seem a bit childish, even somewhat like baby talk. I can assure you it is anything but.

These words are used consonantly in all forms of adult conversation and correspondence. You will see and hear these sorts of words in casual conversation as well as in full-on formal speeches and all-out academic writing.

Giseigo are a fundamental part of the Japanese language.

Kana: the key to giseigo

Giseigo are almost exclusively written in kana. Yeah, sure, the dictionary may list some kanji that can technically be used to write them, but, well, let’s put it this way: If your Japanese is at the level that you’re still reading this article, you don’t need to worry about that.

If you want to be able to read anything in Japanese, but especially giseigo, then you need to learn your kana.

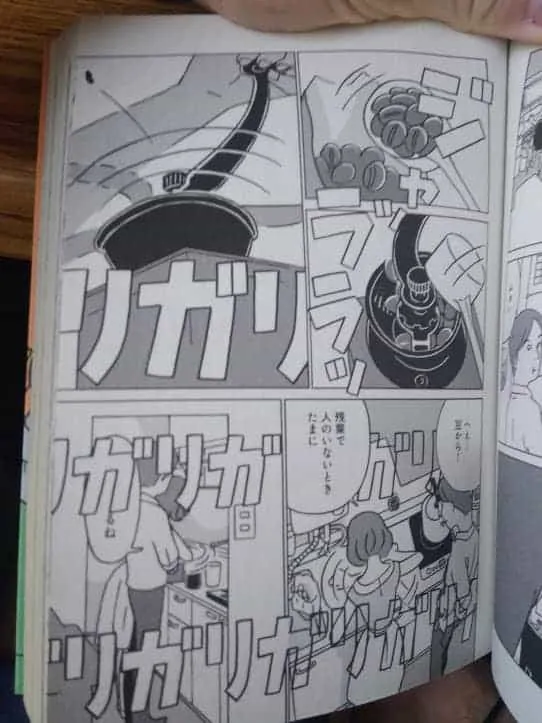

If you tend to read some {ahem} “early release” translated manga, you may notice that the “action sounds” in the background of the comic panels are usually untranslated.

If you want to get the full feel of the manga you’re reading, even if you’re reading them in English you should learn your kana just to be able to get a feel for the sound effects the creators wanted you to experience.

What are the kana? Well, they’re sort of like the alphabet for Japanese.

The kana consists of two mirror-image characters (kind of like how we have upper and lower case letters… kind of), the hiragana and katakana.

Each one has 46 characters, but several are either exactly the same (へ/ヘ), or very similar (せ/セ). You can learn all 92 in a week of concentrated studying.

Some extra notation to help you along

Many giseigo end with the small-tsu character っ. This indicates a short stop at the end of the word. It’s very clipped. Think about closing your throat off at the end of the word to create the clipped sound.

ー is a long dash that just extends a vowel sound.

~ is like the dash, but wavy. It is what it looks like—a sort of up and down inflection in the word.

Finally, you’ll see smaller versions of the kana. For example, あああぁァァ! is something you might read in manga.

Each of those characters represents the same sound, but it gives the sense of the exclamation trailing off, and perhaps (with the switch to katakana for the last two characters) becoming strained at the end.

Giseigo: Sounds from living things

|

ふわあ |

fuwaa |

Yawning |

|

はははは |

hahahaha |

Laughter |

|

ぱちぱち |

pachipachi |

Clapping |

|

ごほん |

gohon |

Cough |

|

わんわん |

wanwan |

Dog’s bark |

|

にゃん |

nyan |

Cat’s meow |

|

ぶーぶー |

buubuu |

Pig’s oink |

|

もーもー |

moomoo |

Cow’s moo |

|

こけこっこ |

kokekokko |

Chicken’s cluck |

|

ひひいん |

hihiin |

Horse’s neigh |

|

かーかー |

kaakaa |

Crow’s kaw |

|

ブーン |

puun |

bee’s buzz |

|

がーがー |

gaagaa |

Duck’s quack |

|

ちゅんちゅん |

chunchun |

Bird’s chirp |

|

めーめー |

meemee |

Sheep’s baa |

|

うきうき |

ukiuki |

Monkey’s howl |

|

ちゅーちゅー |

chuuchuu |

Mouse’s squeak |

|

げろげろ |

gerogero |

Frog’s croak |

|

ほーほー |

hoohoo |

Owl’s hoot |

|

がおー |

kaoo |

bear’s roar |

And, good news, the Japanese have revealed the answer to a long-standing mystery! Indeed, they know what the fox says! And it’s コンコン (kon-kon).

Giongo: Real sounds made by inanimate things

|

バンバン |

Ban-ban |

sound of gunshooting |

|

ばしゃっ |

basha- |

Water scattering, splashing forcefully |

|

ポツポツ |

Botsu-botsu |

sound of water dripping or rain drops |

|

ドカン |

dokan |

the sound of an explosion |

|

ぎしぎし |

Gishi-gishi |

Grinding & squeaking (like teeth) |

|

ごろごろ |

Goro-goro |

A boulder or rocks tumbling down a hill |

|

こぽこぽ |

kopokopo |

Water bubbling gently |

|

めらめら |

Mera-mera |

Suddenly bursting into flames |

|

ぱたぱた |

Pata-pata |

Cloth lightly flapping in the wind |

|

ポキっ |

poki- |

something small snapping |

|

ぴゅーぴゅー |

Pyuu-pyuu |

Strong, continuous, and cold wintry winds |

|

さくさく |

Saku-saku |

Stepping on soft dirt or sand |

|

たん |

tan |

feet stomping; something put down hard |

|

たたたた |

tatatata |

Running at full speed |

|

ざーざー |

Zaa-zaa |

Lots of heavy rain pouring down |

|

ズガ |

zuga |

sound of a hard blow |

Gitaigo: Sound of phenomena

|

バタバタ |

Bata-bata |

clattering, rattling |

|

べとべと |

Beto-beto |

Sticky with sweat or blood |

|

びしょびしょ |

Bisho-bisho |

Horribly soaked by a large amount of water |

|

びっしょり |

bisshor |

to be soaked |

|

ボロボロ |

Boro-boro |

Worn-out, ragged, tattered |

|

ちくちく |

Chiku-chiku |

prickly, like a porcupine or cactus |

|

でこぼこ |

Deko-boko |

Uneven ground |

|

どきどき |

to throb with a fast heart-beat |

|

|

フワフワ |

Fuwa-fuwa |

bouyant, fluffy |

|

がたがた |

Gata-gata |

A road that isn’t paved |

|

ガヤガヤ |

gaya-gaya |

the sound of crowd, mob |

|

ぎらぎら |

Gira-gira |

A glint in your eyes |

|

ぎりぎり |

Giri-giri |

at the last moment |

|

ぐるぐる |

Guru-guru |

going around in circles (literally and figuratively) |

|

はたはた |

Hata-hata |

fluttering in the wind |

|

ひんやり |

hinyari |

Feeling cool |

|

ほかほか |

Hoka-hoka |

A warm body or food |

|

いちゃいちゃ |

icha-icha |

the sound of two people making out |

|

いらいら |

ira-ira |

to be fretful, irritated |

|

いそいそ |

iso-iso |

to move around with liveliness |

|

じんわり |

jinwari |

Soaking slowly with sweat or tears |

|

かっか |

kakka |

burning hot and red |

|

コロコロ |

Koro-koro |

lightly rolling |

|

ムキムキ |

muki-muki |

bulge ripple, muscular physique |

|

ムシャムシャ |

musha-musha |

the sound of someone eating or munching on something |

|

むしむし |

Mushi-mushi |

Too much warmth, unpleasantly hot |

|

ニコニコ |

Niko-niko |

smiling |

|

ニョロニョロ |

Nyoro-nyoro |

long/thing; wriggling motion |

|

おどおど |

odo-odo |

to feel uneasy |

|

ぴかぴか |

pika-pika |

to shine, sparkle, glitter |

|

ピリピリ |

Piri-piri |

stinging from spicy food |

|

ぴょんぴょん |

pyon-pyon |

jumping |

|

さんさん |

San-san |

Lots of shining sunlight |

|

さらさら |

Sara-sara |

smooth and soft |

|

さわさわ |

Sawa-sawa |

rustling of leaves int eh wind |

|

しゃきしゃき |

Shaki-shaki |

watery/crunchy texture of fresh food like lettuce or a bell pepper |

|

しっかり |

shikkari |

solid foundation; trustworthy |

|

しとしと |

Shito-shito |

drizzling |

|

つやつや |

Tsuya-tsuya |

beautifully glistening |

|

ウハウハ |

uha-uha |

jumping |

|

うかうか |

uka-uka |

to be careless or absentminded |

|

うとうと |

uto-uto |

to doze off |

|

うつらうつら |

utsura-utsura |

to drift between sleep and wakefulness |

|

ワイワイ |

wai-wai |

the sound of children playing |

|

ざーざー |

Zaa-zaa |

raining heavily |

Gijogo: Sound of feeling

|

あたふた |

Ata-futa |

Running about in a rush |

|

あわあわ |

Awa-awa |

Losing a grasp on your senses |

|

がんがん |

Gan-gan |

pounding headache |

|

いらいら |

Ira-ira |

annoyed, irritated |

|

くよくよ |

Kuyo-kuyo |

Worrying about past trivial stuff |

|

もじもじ |

Moji-moji |

Unable decidedue to shyness |

|

もやもや |

Moya-moya |

wondering what to do |

|

さっぱり |

sappari |

feeling refreshed/relieved |

|

しんみり |

shinmiri |

Lonely, solemn |

|

しょんぼり |

shonbori |

despondent |

|

うきうき |

Uki-uki |

Happy, lighthearted, hope-filled |

|

うっとり |

uttori |

fascinated by something beautiful |

|

わくわく |

Waku-waku |

Excited from anticipation, or pleasure |

|

ずきずき |

Zuki-zuki |

Throbbing, deep pain |

Giyogo: Sound of motion

|

ぼーっと |

bootto |

absentmindedly |

|

ぶるぶる |

Buru-buru |

Trembling from cold, fear, or anger |

|

がくがく |

Gaku-gaku |

Joints, like knees, shaking |

|

ゴシゴシ |

Goshi-goshi |

scrubbing |

|

ぐんぐん |

Gun-gun |

vigorously (used with plants and animals) |

|

ぐっすり |

gussuri |

Completely and totally asleep |

|

ぐーたら |

guutara |

Not having the willpower to do anything |

|

きょろきょろ |

Kyoro-kyoro |

Turning around looking around restlessly |

|

モミモミ |

Momi-momi |

massage |

|

のろのろ |

Noro-noro |

Proceeding at a snail’s pace, slow and sluggish |

|

ぷくぷく |

Puku-puku |

foam/bubble action |

|

すたこら |

sutakora |

Fast paced, eager walking |

|

うろうろ |

Uro-uro |

Wandering aimlessly |

|

うとうと |

Uto-uto |

Half asleep, nodding off |

|

わいわい |

Wai-wai |

Clamorously |

Some written examples of giseigo

あの犬、一日中ワンワンワンワン吠えてるんだから。

ano inu, ichi-nichi-jyu wan-wan-wan-wan hoeterundakara.

That dog has been barking ‘Ruff-ruff-ruff-ruff!’ all day long.

ダイナマイトがドカンと爆発した。

Dainamaito ga dokan to bakuhatsu-shita.

The dynamite exploded with a bang.

うとうとしているうちに駅を通りすぎてしまったらしい。

Uto-uto-shiteiru uchi-ni-eki wo torisugiteshimattarashii.

I must’ve passed my station while dozing off.

今日一日当ても無くうろうろした。

Kyo-ichi-nichi totemonaku urouro-shita.

I wandered about aimlessly all day.

彼女は馬鹿らしい質問をされていらいらした

Kanojo wa baka-rashii shitsumon wo sarete ira-ira-shita.

She was annoyed by the stupid question.

Real life examples!

Here’s a timely example:

Across numbers 3-9, we see four different examples of giseigo.

あわ立てプクプク

awatate puku-puku

Bring soap to a foam

手のこうモミモミ

te-no-kou momi-momi

Massage the back of your hand

ゆびのあいだモミモミ

yubi-no-aida momi-momi

Massage between your fingers

おやゆびくるくる

oya-yubi kuru-kuru

Wash all around your thumb

てのひら・ゆびのさきごしごし

te-no-hira/yubi-no-saki goshi-goshi

Scrub your palms and fingertips.

手くびくるくる

te-kubi kuru-kuru

Wash all around your wrists.

しっかりながして

shikkari nagashite

Rinse completely

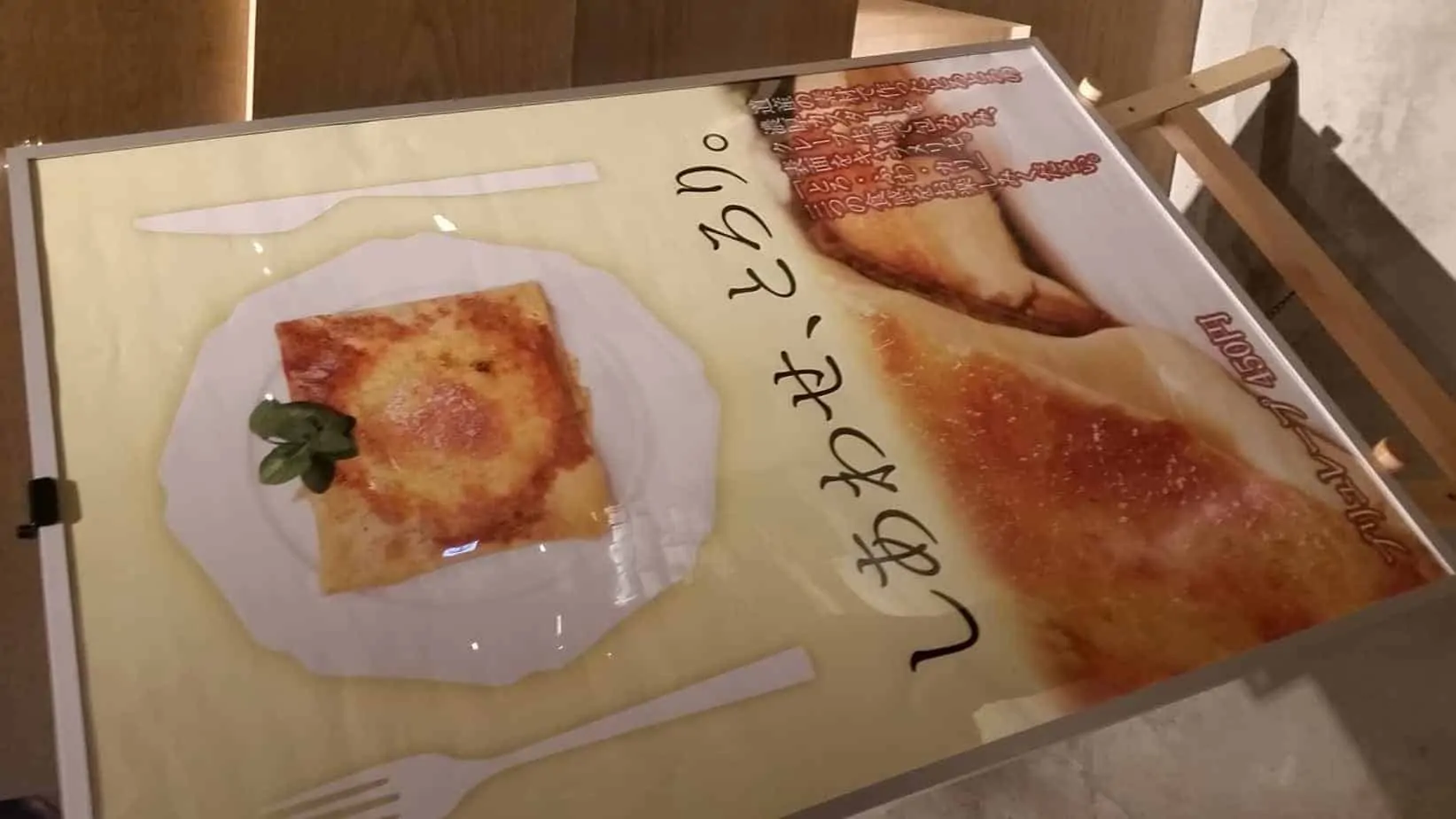

しあわせ、とろり。

Shiawase, torori.

Happiness, thick.

道産の素材で作ったとろとろの濃厚カスタードを表面をキャラメリゼ。

Dosan-no-sazai de tsukutta toro-toro no noko kasutaado wo hyomen wo kyaramerize.

Made from native Hokkaido ingredients, the surface of the sticky, rich custard is caramelized.

「とろ・ふわ・カリ」三つの食感をお楽しみください。

“Toro, fuwa, kari,” mittsu no shokkan wo o-tanoshimi-kudasai.

“Rich, fluffy, caramel,” enjoy all three textures.

ガチャポン

gacha-pon

This word is the name of those capsule toy machines. The “gacha” part is the sound of turning the knob, and the “pon” sound is the capsule popping down.

チーズたっぷり

chiizu tappuri

Lot’s of cheese

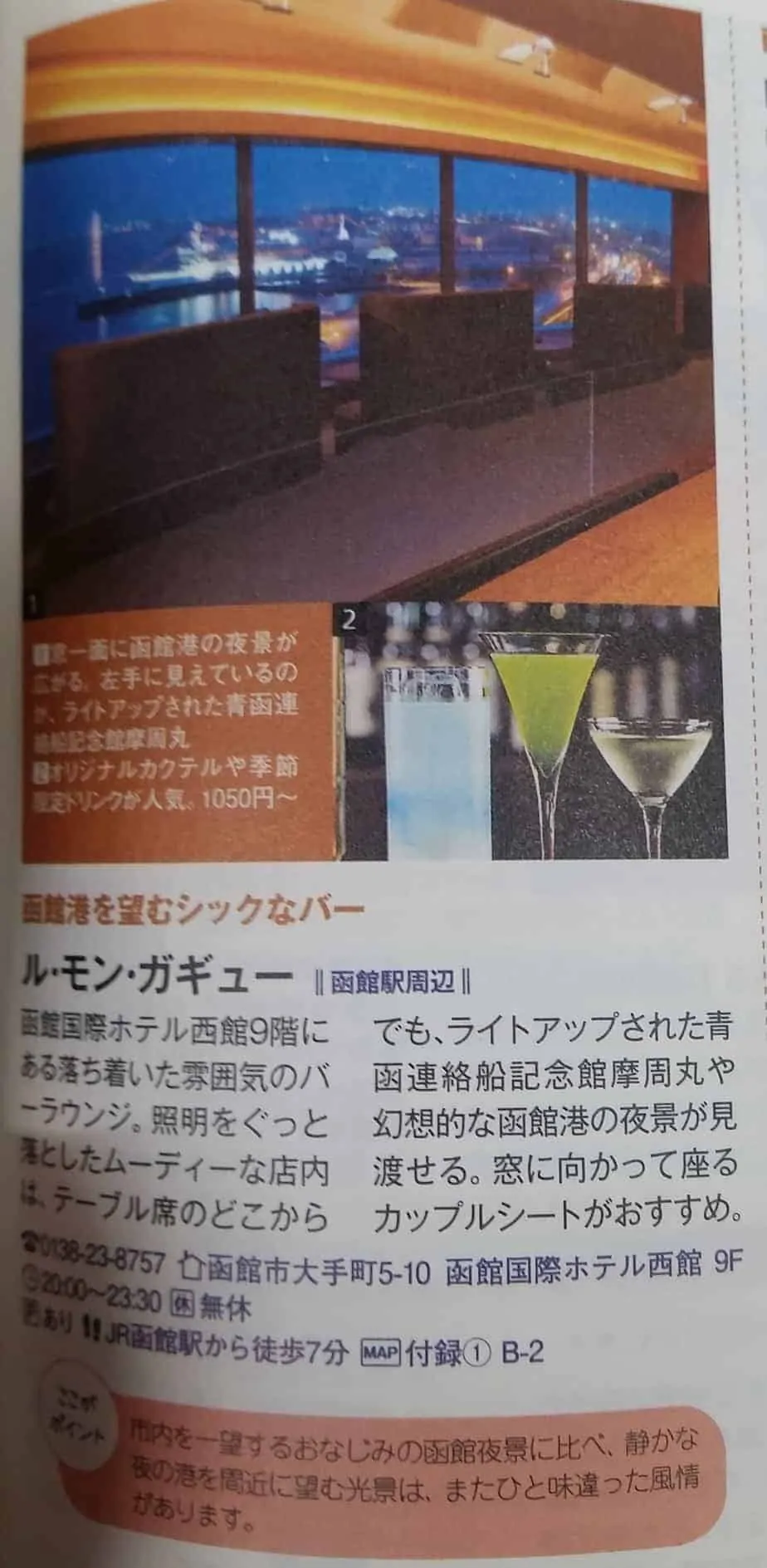

照明をぐっと落としたムーディーな店内は、テーブル席のどこからでも、ライトアップされた青函連絡船記念館摩周丸や幻想的な函館港の夜景が見渡せる。

Shomei wo gutto otoshita muudeii-na tennai wa, teeburu-seki no dokokara demo, raitoappu-sareta seikan-renrakusen-kinenkan-mashumaru ya gensoteki-na Hakodate-ko no yakei ga miwatariseru.

Illuminating the perfectly atmospheric restaurant, anywhere you sit you can look out over the lit up Seikan Ferry Memorial Ship “Mashu Maru,” and the fantastic Hakodata harbor night view.

キャンキャンキャンキャン

kyan-kyan-kyan-kyan

Yap yap yap yap

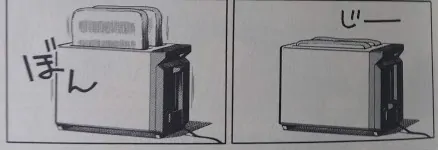

For these next two, trying to have a direct translation isn’t practical. Instead, look at the pictures, read the transliteration (if you can’t read kana yet), and try to <i>feel</i> the way the sound-symbolism works here.

Some Japanese text and conversation involves made-up sound-symbolism (just like in American comic books), but the feeling of how certain sounds express our world is so deeply ingrained in the language, that it makes perfect sense to native speakers.

じー

jii

ぼん

bon

ジャッ

JA-

ララッ

RARA-

ガリガリガリガリガリガリ

GARIGARIGARIGARIGARIGARI

身体をビリビリと震わせる轟音。

Shintai wo biri-biri to furuwaseru go-on.

My body trembled with the rumbling roar.

にょきにょきと雲のように噴出する白煙。

Nyoki-nyoki to kumo-no-yoni funshutsu-suru hakuen.

White smoke spewing out like clouds, on and on.

小惑星探査機「はやぶさ」やさまざまな月・惑星探査機、科学衛星による観測で、宇宙の謎がどんどん解明されつつある。

Shouwakusei-tansaki “Hayabusa” ya sama-zama-na tsuki/wakusei-tansaki, kagaku-eisei-niyoru kansoku de, uchu-no-nazo ga don-don kaimei-sare-tsutsu-aru.

The asteroid probe “Hayabusa,” various moon and planetary probes, and scientific observation satellites, are all continuously unravelling the mysteries of the universe.

ばったん! (Battan!)

There you go folks. Everything you need to get started on your Japanese onomatopoeia/giseigo journey! Make sure to drop a comment with any interesting, cool, confusing, or strange Japanese onomatopoeia you’ve found!

Hey fellow Linguaholics! It’s me, Marcel. I am the proud owner of linguaholic.com. Languages have always been my passion and I have studied Linguistics, Computational Linguistics and Sinology at the University of Zurich. It is my utmost pleasure to share with all of you guys what I know about languages and linguistics in general.