In this article, we’re going to look at cursive writing — you know, the fancy, loopy script your grandparents used on birthday cards.

This will take us through 19th-century schoolrooms, wartime letters, mid-century business etiquette, and straight into the modern graveyard of forgotten skills.

Let’s start with a very broad overview of what cursive was actually meant to do.

What Even Is Cursive, Anyway?

Cursive is a style of handwriting where letters are connected for speed and flow.

It’s also sometimes called “joined-up writing,” especially in British English.

The whole idea was to minimize pen lifts and make longhand writing quicker and more efficient. Great in theory. Awful when you had to read your friend’s cursive notes under exam pressure.

Why Cursive Was the OG Productivity Hack

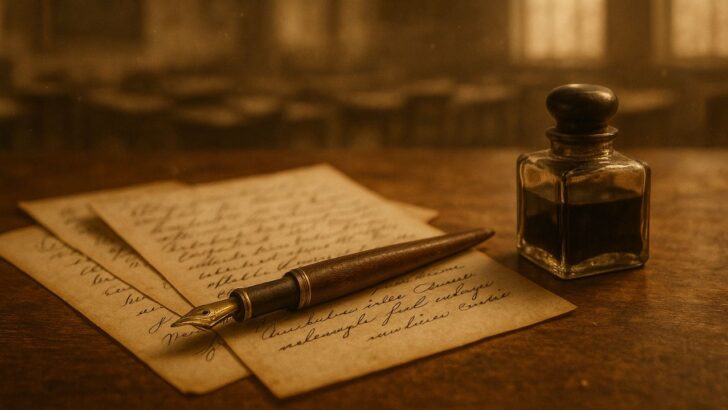

Back before laptops, phones, and even typewriters, writing fast mattered.

You needed to take notes. Copy texts. Send letters. And if you lifted your quill between every letter, you’d be writing until the ink dried out (which it often did).

Cursive solved that.

The earliest cursive scripts were developed by Roman scribes. Then came more decorative versions in the Middle Ages, followed by a full-on penmanship craze in the 17th to 19th centuries.

By the time the 1800s hit, cursive wasn’t just practical — it was expected.

Cursive Wasn’t Just Writing. It Was a Personality Test.

Let’s talk about Spencerian Script and Palmer Method.

These were taught in schools across America. Think perfectly round loops, rhythmic strokes, and letters that looked choreographed.

Penmanship wasn’t handwriting. It was character training.

Kids were judged by how neat their cursive was. You practiced it daily. Entire workbooks were devoted to it. It was a legit skill. Employers cared. Teachers obsessed. Parents framed samples.

And your signature? That was your identity. Fancy, fast, and full of flair.

The Machines Arrived — and Cursive Didn’t Stand a Chance

Enter: the typewriter.

Suddenly, speed and legibility weren’t about loops — they were about tapping keys.

But cursive still hung on. It was too embedded. Too aesthetic. Still powerful in business and personal correspondence.

Then came the computer.

Then smartphones.

Then email.

By the 2000s, cursive wasn’t just fading — it was disappearing. Quietly. Almost politely.

Curriculums dropped it. Standardized tests ignored it. Kids asked, “What’s the point?”

And the thing is — they had a point.

Can Gen Z Even Read This Script? (Spoiler: Not Really)

In many cases? Nope.

Show a handwritten note from the 1950s to a 14-year-old, and you may as well have handed them a cryptic runestone.

Cursive is now functionally a code. A slow one. A pretty one. But still — a code.

And while some states brought it back into classrooms (looking at you, Texas), it’s more of a nostalgic gesture than a practical one.

Cursive is no longer a tool. It’s a relic.

More Than Just Loops: The Emotion Inside the Ink

Here’s the twist: Cursive was never just about speed. It was about style. Identity. Emotional weight.

You could write the same sentence in print or cursive — and it would feel different.

Cursive adds tone. Personality. A bit of humanity.

That’s why wedding invites still love it. Why your grandma’s recipes feel more meaningful handwritten. Why old letters hit harder.

It’s tactile. And kind of poetic.

Is Cursive Dead? Kind Of. But Also Not Really.

Cursive isn’t completely dead. It’s just no longer required.

It lives on in:

- Signatures (barely)

- Journals

- Artsy bullet notebooks

- Tattoo scripts

- Instagram handwriting reels

But let’s be honest — for most people, cursive is a ghost. A style we respect, vaguely remember, and maybe wish we still had time for.

If you want to bring it back, go for it. But don’t expect the world to follow.

We buried cursive for a reason. But there’s no rule against visiting the grave.

Hey fellow Linguaholics! It’s me, Marcel. I am the proud owner of linguaholic.com. Languages have always been my passion and I have studied Linguistics, Computational Linguistics and Sinology at the University of Zurich. It is my utmost pleasure to share with all of you guys what I know about languages and linguistics in general.