However, all is not what it seems. In Japan, you drive on a “blue” light. You delight in a “pink” peach. You’re blinded by the noon’s “red” sun.

As with any cultural identifier, color is not proverbially set in stone. In other words, our understanding and use of color changes based on culture and, perhaps more importantly, language.

There are a million reasons why… from historical interactions with other cultures to forming different types of color groupings to not giving individual colors a name at all.

If you pay attention closely, you can see the different ways in which cultures recognize, describe, and even smell color.

For most of you reading this, Japanese‘s colors will be a little surprising.

How do you say the different colors in Japanese?

The core colors in Japanese are shiro (白, white), kuro (黒, black), aka (赤, red), and ao (青, blue). Other common colors include midori (緑, green), ki-iro (黄色, yellow), murasaki (紫, purple), cha-iro (茶色, brown), hai-iro (灰色, gray), kin-iro (金色, gold), gin-iro (銀色, silver), orenji (オレンジ, orange), and pinku (ピンク, pink).

In the beginning…

One difficulty with talking about ancient Japanese is that they didn’t develop a writing system until pretty far into the development of their civilization.

In fact, they didn’t really develop one at all. They took it. From China. And then they mapped the words they already had onto Chinese characters called kanji.

An ancient Japanese might call this view of the past black and blue, or dark and vague. See, way back in the murky depths of Japanese’s linguistic history, color derived from just four visual properties—light, dark, clear, and vague—which then evolved into the colors we know today

| Ancient | Modern | Kanji | Romaji |

| Light | Red | 赤 | aka |

| Dark | Black | 黒 | kuro |

| Clear | White | 白 | shiro |

| Vague | Blue | 青 | ao |

*Japanese “ao” is not quite what we know as “blue”. It also includes green. I’ll explain further down.

These concepts are so foundational that just about any name, or any famous saying, that includes a color is sure to include only these.

These are also the only colors that can be properly paired with ma- (真っ), a prefix that means something like “pure” or genuine.

| Bright red | 真っ赤 | makka |

| Pitch black | 真っ黒 | makkuro |

| Bright white | 真っ白 | masshiro |

| Deep blue | 真っ青 | massao |

Shades of the first three were used to showcase religion and the higher orders of life, while blue was primarily used for representing secular life.

The red-lacquered tools of the rich, the crimson sheath of the samurai sword, the shifting hems of the shrine maidens’ hakama, and the bold spread of the Torii gates; the golden white of gilding, the hearty fibers of shimenawa purification ropes, the bright white of magical shide paper, and the pure salt that dusts the sacred floor; and then the austere black, heart of dignity, the shade of Buddhist monks’ robes, and the kimono that carries one’s family crest.

Secular blue was saved for porcelain, fine woodblock prints, and daily-wear kimono.

But that’s just the beginning…

The Politics of Color

All other colors derived from within the spectrum of these original four. And trust me, there are many more colors.

The Japanese color system, listing nearly 500 colors, has been in use since the Asuka period (538-710 CE).

This list was important not just for keeping track of such a wide array of hues, but also served a political purpose.

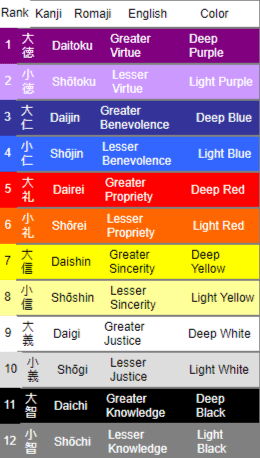

When this more advanced color system kicked off, it coincided with the establishment of the Japan’s own “Twelve Level Cap and Rank System,” or kan’i junikai (冠位十二階, かんいじゅうにかい).

This was a new governmental system that began in 603 and was based on old Confucian principles adopted from China and Korea.

For each of these ranks, a color was assigned.

Source: Wikipedia

Beyond this, there were also forbidden and permitted colors in the courts of ancient Japan.

“Forbidden colors” or kinjiki (禁色, きんじき) were only worn by the imperial family and those of high enough rank.

Those of lower rank were only allowed “permitted colors” or yurushiiro (許し色, ゆるしいろ). The “forbidden” colors, for your amusement:

[table id=15 responsive=scroll/]

Beyond these colors there are, like, 480 or so more in the official list. You can find the complete list of traditional colors (with their modern hex-codes and RGB patterns included!) on Wikipedia.

For the most part, the language of color was relatively static until the last hundred and fifty years.

The introduction of widespread foreign influence began to change that.

This is in part due to the introduction of crayons into the Japanese market in the first half of the 1900s and American educational material post World War II.

For many of the colors today, the western pronunciation is just as commonly used as the original Japanese.

の color anymore…

Grammatically speaking, color in Japanese comes in two types. There are no-adjectives (a sort of noun-cum-adjective) and i-adjectives (“true” adjectives).

While all colors can be turned into no-adjectives, only a select few are used as i-adjectives.

Let’s start with no-adjectives. If you take off the no or “の” (which conveniently looks a little like an ‘n’ in English), these words become nouns.

The の makes them adjectives, and thus they require a noun after the の.

Typically, you will see these words paired with -iro (色, いろ), the literal translation for color.

If you look closely, you will notice that green and purple do not include the second Kanji. It’s more natural this way, although as with any language, this rule is sometimes broken.

| 黄色* | ki-iro | yellow |

| 緑 | midori | green |

| 茶色 | cha-iro | brown |

| 紫 | murasaki | purple |

| 桃色 | momo-iro | peach-pink |

| 灰色 | hai-iro | gray |

| 鼠色 | nezumi-iro | mouse gray |

| 金色 | kin-iro | gold |

| 銀色 | gin-iro | silver |

| ホワイト | howaito | white |

| ブラック | burakku | black |

| レッド | reddo | red |

| ブルー | buruu | blue |

| オレンジ | orenji | orange |

| ピンク | pinku | pink |

| ネイビー | neibii | navy |

| ブロンズ | buronzu | bronze |

*Technically, 黄色 is a na-adjective, but for our purposes this is a negligible point

The basic structure for no-adjectives is Color + の + subject.

桃色の花

Momoiro no hana

Pink flower

私の紫の車です。

Watashi no murasaki no kuruma desu.

It’s my purple car.

… い want to paint it black

Adjectives, as mentioned earlier, are slightly different from nouns.

Red, black, blue, and white—the four original—are the only colors that take the ending –い (-i).

| 青い | aoi | blue |

| 赤い | akai | red |

| 黒い | kuroi | black |

| 白い | shiroi | white |

The basic structure for i-adjectives is Color + noun.

赤い物

Akai mono

Something red

私の白い車です。

Watashi no shiroi-kuruma desu。

It’s my white car.

Speaking of colorful…

Now that I have thoroughly confused you with grammar, let’s take a step back and focus on our vocab.

Truly, the only logical place to begin is with the word for color itself.

You will see 色 pronounced in two ways, either as “iro” or as “shiki.” However, the former is far more common when discussing color.

This one is super useful—great for talking about color.

Words that include the kanji 色 and do not refer to a specific color are various and many. Let’s take a look at a few to try and get a feel for the word.

| 色合い | iroai | tint, shade, hue |

| 色あせた | iroaseta | Faded color |

| 色とりどり | irotoridori | Colorful |

| 多色の | tashokuno | Multi-colored |

| 虹 | niji | rainbow |

| 濃い色 | koi-iro | dark color |

| 薄い色 | usui-iro | light color |

Not to be confused…

This kanji also appears in the word 色々な or ‘iroirona’, which means “a variety of” in English.

This is not a direct reference to color, unless of course you tack on another 色 at the end. And now you’re just trying to make trouble.

Off-color

Speaking of troublemakers, there is something a little naughty about 色.

With an excess of imagination you might just be able to see one person クand another person bent double 巴 in the middle of the upside-down mambo.

Off-color as this reference may seem, it has its basis in history and the etymology of the character. Way, way back, the character meant “siblings.”

This sense of things became “familial love” which soon lost all semblance of the familial and became just, well, the most colorful kind of love.

This gradual evolution, from family, to amorous affection, to beauty, eventually led to its current meaning of “color.” That said, it still carries some of that ancient meaning in a few words.

Let’s take a peek:

| 色っぽい | iroppoi | sexy |

| 色気 | iroke | sexual charm |

| 色男 | iro-otoko | playboy |

| 色情 | shikijyou | sexual desire |

Speaking of color…

Here are some useful phrases you can use to talk about color:

なにいろですか。

Nani-iro desu ka?

What color is it

みどりです。

Midori desu.

It’s green.

私の好きな色は緑です。

Watashi no sukina‐iro wa midori desu.

My favorite color is green.

Of Light and Dark, Good and Evil….

While it is true that white, or ‘shiro’, is symbolic of purity and honesty, black, or ‘kuro’, doesn’t have the same negative meaning  that it does in other cultures. Rather, black is the color of dignity and formality, a ward against evil. These two colors are often represented together in religious ceremony and art.

that it does in other cultures. Rather, black is the color of dignity and formality, a ward against evil. These two colors are often represented together in religious ceremony and art.

Shinto shrines, torii gates, and other sacred landmarks are often decorated with twisted “enclosing ropes” or shimenawa (注連縄, しめなわ) which protect against evil spirits and indicate a pure or sacred space.

They are a common New Year’s decoration. Traditionally, they were woven from hemp, but nowadays due to legal restrictions are more frequently made from rice or wheat straw. They are decorated with white zig-zag folded paper streamers known as shide.

Another example of this white purity is how it’s used in traditional weddings.

There are several types of wedding kimonos, the most traditional of which are pure white. One that stands out is the shiromuku (白無垢, しろむく).

The shiromuku was originally worn in samurai families and dates back as far as the Heian period, though nowadays even common people can wear them.

Everything—from the large, egg-shaped hood, to the delicate accessories, to the furisode and obi—are white.

Eye-Tooth of the beholder

Color isn’t always used in the way we would expect it to be. People used to paint their teeth black in a custom called o-haguro (お歯黒), literally “teeth-black.”

It was popular as a show of beauty among women and, to a lesser extent, men up until the end of the Meiji era (1868-1912).

From a distance, darkened teeth simply disappear.

While the thought of putting dissolved iron mixed with vinegar on your teeth causes me personally to cringe, it turns out it actually prevents tooth decay.

And, in the olden days, it also might attract a mate, or at least a wealthy patron!

Tickled Pink

Shades of pink color Japanese society, from fairy tales to flowers, children’s toys to erotica. Originally perceived as a mere shadow of red, there are many descriptive terms that describe the color today, with ピンク or pinku recognized as the most widely used. But, just for fun, let’s take a look at some other ways shades of pink are represented in Japan…

Shades of pink color Japanese society, from fairy tales to flowers, children’s toys to erotica. Originally perceived as a mere shadow of red, there are many descriptive terms that describe the color today, with ピンク or pinku recognized as the most widely used. But, just for fun, let’s take a look at some other ways shades of pink are represented in Japan…

To begin, think about cherry blossoms, or, as they’re known in Japan, “sakura” (桜, さくら).

In Japan, they represent the transience of life, the week-or-so-long life of the blooms reflecting the brief life of man.

But, beyond those borders, they’re mostly known for their beautiful shade of pale pink. And, well, in Japan they are too, sorta.

It’s not super-common, but you’ll occasionally see the term 桜色 used to describe something that has the delicate, pale-pink color of that oh-so-lovely-flower.

Alright, let’s kick the pink up a notch! Peaches! Peaches are such a beloved fruit in Japan, that they’ve even spawned their own beloved mythology: the adventurous Momotaro, aka “Peach Boy.”

The word “momo-iro” (桃色, ももいろ) is used to describe the color of a peach or a peachy pink. Although peaches are extremely popular, the use of the word to describe color isn’t.

You will see it sometimes when describing peach blossoms, kimono, or the color of flesh. Um… yum?

彼女のほおは薄く桃色に染まっていた。

Her cheeks were tinged with pink.

As I mentioned earlier when discussing iro (色, いろ) Japan uses color to express off-color subjects.

Want to watch low-budget, soft-core erotica? You should try out a pink film (ピンク映画, ピンクえいが).

Nudity is a core feature to these movies, hence the name. As you might guess, you will see lots and lots of pink.

Time to roll out the red carpet…

In Japan, red, or akai (赤い, あかい), is the color of the sacred and of wealth, of aggression and nationhood.

Shrines and torii gates are painted bright red.

Vermilion, sometimes referred to as Chinese red, is used for women’s combs and hair accessories, for samurai sword sheaths, and for numerous interior decorations.

This can range from a vivid red to reddish orange. It is one of the original four, and is almost gaudy where the other three are more subtle.

In Japanese folklore, soulmates were said to be joined by an invisible red string. This string is called akai-ito (赤い糸, あかいいと) and each person had one end of this string tied around their pinkie or little toe.

This “red string of fate” can be seen in the popular 2016 movie Your Name by Makoto Shinkai in which two star-crossed lovers are tied together across time and space.

In Japanese finance, the English expressions “in the red” and “in the black” find their match in akaji (赤字, あかじ) and kuroji (黒字, くろじ), respectively.

Red and white are generally paired together for festive or auspicious occasions. Kouhaku (紅白,こうはく) is the combination of kou, or crimson, and haku, or white.

During festivals, you can buy red and white candy sticks at children’s festivals, red and white egg-shaped mochi, and even red and white oval rice cakes!

Kouhaku curtains (紅白幕) are hung to give a festive appearance on formal occasions, such as graduation ceremonies.

Here’s some more words derived from red:

| 赤々 | aka-aka | bright red |

| 赤信号 | aka-shingou | red traffic light |

| 赤ちゃん | aka-chan | infant |

| 紅白 | kouhaku | red and white |

| 赤字 | akaji | in the red |

| 赤い糸 | akai-ito | red string of fate |

Cha Time

Brown, or cha-iro (茶色), is constantly present both in nature and in our everyday surroundings.

Yet, it was not included in one of the primary four colors. Rather it was considered a shade of red and blue.

It is very much used as a symbolic reflection of the natural environment. It was a fairly popular color to wear during the Edo era (1603-1868) among common people.

But that first kanji in 茶色 doesn’t actually mean brown. It means tea. But wait, isn’t tea black or green?

Well, yes, but in Japan it is just as often brown. Houjicha, or roasted green tea, is one such popular tea, with a deep reddish-brown color.

There’s also genmaicha, made with roasted rice.

Kogecha-iro(こげ茶色, こげちゃいろ) is a dark brown or olive tone color. It is used to describe hair color. This is a popular option for hair dye among Japanese people.

You may also hear the loan-word ブラウン (buraun) in conversation, but it’s almost certainly just a name, like Mr. Brown, and not related to the color.

A royal welcome

The color of royalty since prior to 600AD, murasaki-iro (紫色) could only be worn by those “born to the purple”.

It wasn’t until the Edo era that the color passed on from the upper echelons of imperial society to ordinary people.

Edo-Murasaki (江戸紫) is purple-bluish color while previous purples were more reddish in tone.

Shiden (紫電) is not a commonly used word. It’s made up of purple (紫) and electricity (電), and refers to either purple lightening or the flash of a blade.

It’s also the name of a fierce, late World War II fighter plane, considered one of the best in the Japanese arsenal.

Here’s a few more purple-based words:

| 紅紫 | koushi | magenta |

| 紫色 | Shiiro | Female Given name |

| 菫色 | sumire-iro | violet |

| ラベンダー色 | rabenda-iro | lavender |

| 紫外線 | shigaisen | UV rays |

Once in a Bluish-Greenish moon

As the idiom goes…it is always greener on the other side, which just so happens to be blue in the Japanese dictionary.

That’s right. Green is just another shade of blue, at least historically speaking.

This explains the seeming inconsistencies in commonly used words and phrases.

The distinction between green and blue really began to take an effect after the turn of the century with the importation of crayons starting in 1917 and new educational material in 1951.

Taking this into consideration you might be surprised that the word for green, midori, dates as far back as the Heian Period.

It represents “freshness” and “youthful spirit”. As you’ve probably guessed, it’s mostly used in reference to greenery, although we will put aside for the moment that said greenery produces “blue leaves” (青葉, あおば) in springtime.

Common Blue/green “inconsistencies”:

| 青りんご | ao-ringo | Granny Smith Apples |

| 青野菜 | ao-yasai | blue veggies, like broccoli, lettuce, & spinach |

| 青臭い | ao-kusai | “smell of blue”; inexperienced; greenhorn |

| 青信号 | ao-shingou | “green” traffic light |

| 緑の黒髪 | midori no kurokami | Young women with shiny raven black hair |

So what is actually blue (to a non-Japanese eye)?

| 紺 | kon | navy blue |

| 水色 | mizu-iro | pale blue |

| 蒼然 | souzen | blue-ish |

| ブルー | buruu | feeling down, color blue |

Blue and green are probably the most difficult colors to get the hang of in the Japanese language, so don’t feel bad if you continue to mix things up for a while.

And now a parting gift

I came across this a few years ago and had the chance to practice it on my coworkers. They thought I was the Smoothest Criminal around.

「マイケルジャクソンの好きな色は何ですか?」

「青!」

Maikeru Jakkuson no sukina iro wa nan desu ka?

Ao!

“What’s Michael Jackson’s favorite color?”

“Ao!”

Color in the details yourself

There’s a pretty wide world of color and tradition in Japan, so if you want to get into the nitty-gritty of it, there’s way more to discover out there.

With this article as a starting point, go forth and dive into that bright world!

Related Questions

What color represents Japan?

Since the Japanese national flag is made up of just two colors, red and white, which are also two of the original, native Japanese colors, we could say that red and white most represent Japan.

What color is good luck in Japan?

Furthermore, red and white are the colors of good luck in Japan. You’ll see these at weddings and births, and also on good-luck beckoning cat statues.

Hey fellow Linguaholics! It’s me, Marcel. I am the proud owner of linguaholic.com. Languages have always been my passion and I have studied Linguistics, Computational Linguistics and Sinology at the University of Zurich. It is my utmost pleasure to share with all of you guys what I know about languages and linguistics in general.