Exploring the world’s languages can reveal fascinating and unexpected grammatical structures. While many of us are familiar with the straightforward Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) order of English, some languages challenge these conventions in remarkable ways. From the flexible verb-focused sentences of Tagalog to the complex verb morphology of Navajo, these languages offer a unique glimpse into how humans communicate.

Explore ten languages that defy typical grammar rules and discover how they twist and turn standard linguistic norms.

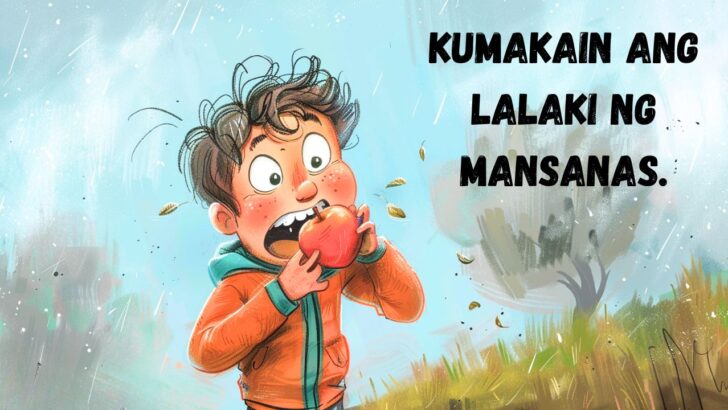

Let’s start with Tagalog!

1. Tagalog

Tagalog, spoken in the Philippines, has a unique focus system significantly affecting verb structure and sentence order. Unlike the typical Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) order in English, Tagalog often uses Verb-Subject-Object (VSO) order, making it particularly interesting for linguists as it’s one of the few languages globally with this structure.

For example:

- English (SVO): “The man (S) eats (V) the apple (O).”

- Tagalog (VSO): “Kumakain (V) ang lalaki (S) ng mansanas (O).”

In Tagalog, the verb “kumakain” (eats) comes first, followed by “ang lalaki” (the man) as the subject, and “ng mansanas” (the apple) as the object.

The focus system also alters the verb based on what is being emphasized:

- Actor-focused: “Kumakain ang lalaki ng mansanas.” (The man is eating an apple.)

- Object-focused: “Kinakain ng lalaki ang mansanas.” (The apple is being eaten by the man.)

Here, “kumakain” changes to “kinakain” to shift the focus from the doer to the action on the object.

This flexibility and the need to adjust verb forms based on focus make Tagalog a fascinating yet challenging language to learn.

2. Pirahã

Pirahã, spoken by the Pirahã people of the Amazon in Brazil, is a language that challenges many conventional grammar rules. One of the most intriguing aspects of Pirahã is its lack of fixed word order, which sets it apart from many other languages. While English follows a strict Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) order, Pirahã allows for much greater flexibility, meaning words can be arranged in various ways without losing meaning.

For example:

- English (SVO): “The man (S) catches (V) the fish (O).”

- Pirahã: “Fish (O) man (S) catches (V).” or “Catches (V) man (S) fish (O).”

This fluid word order reflects the language’s focus on context and situational clues rather than a rigid syntactic structure. Additionally, Pirahã is notable for its limited use of recursion, meaning that sentences typically do not nest clauses within clauses. This feature has sparked considerable debate among linguists, as recursion is often considered a universal property of human language.

Pirahã is exceptionally interesting for linguists due to its unique grammatical structures and the insights it offers into human cognition and language development. Learning Pirahã can be a real adventure, as it requires a shift from conventional grammatical thinking to a more flexible and context-driven approach.

3. Basque

Basque, spoken in the Basque Country straddling Spain and France, is a linguistic enigma with its unique ergative-absolutive alignment. Unlike the nominative-accusative system used by languages like English, where the subject of a sentence is treated uniformly across different types of verbs, Basque distinguishes between subjects of transitive and intransitive verbs.

For example:

- English (SVO): “The woman (S) eats (V) the apple (O).”

- Basque (Ergative-Absolutive): “Emakumeak (ERG) sagarra (ABS) jaten du (V).” (The woman eats the apple.)

In Basque, “emakumeak” (the woman) takes an ergative case when performing a transitive action, whereas “sagarra” (the apple) remains in the absolutive case. This ergative-absolutive alignment is fascinating for linguists because it offers a different perspective on how languages can structure sentences.

Basque also features a complex system of verb conjugations that change based on the subject, object, and indirect object, making it a challenging language to master. For linguists, Basque provides invaluable insights into the diversity and adaptability of human languages.

4. Navajo

Navajo, spoken by the Navajo people in the southwestern United States, features a complex verb structure that challenges conventional grammar rules. Unlike English, Navajo verbs incorporate a wealth of information, including subject, object, tense, and aspect, all within a single word. This polysynthetic nature means verbs can become quite long and detailed.

For example:

- English (SVO): “The man (S) is running (V).”

- Navajo (V-internal complexity): “Ashkii yich’i’ni.” (The boy is running.)

In Navajo, the verb “yich’i’ni” includes information about the subject (the boy), the action (running), and the aspect (ongoing action).

Navajo verbs also utilize prefixes that indicate the relationship between the subject and object, adding another layer of complexity. Navajo is a treasure trove of unique grammatical features for linguists, offering insights into the diverse ways human languages can encode meaning.

5. Icelandic

Icelandic, spoken in Iceland, is known for its highly inflected grammatical system, preserving many features of Old Norse. Unlike English, which has largely shed its case system, Icelandic retains four grammatical cases: nominative, accusative, dative, and genitive. This inflection affects nouns, pronouns, and adjectives, requiring speakers to adjust word endings based on their grammatical role in a sentence.

For example:

- English (SVO): “The boy (S) sees (V) the dog (O).”

- Icelandic: “Drengurinn (NOM) sér (V) hundinn (ACC).”

In Icelandic, “drengurinn” (the boy) takes the nominative case, while “hundinn” (the dog) takes the accusative case. This system adds a layer of complexity to sentence construction, as speakers must be mindful of the case endings to convey the correct meaning.

Icelandic also features a rich set of verb conjugations and strong and weak verb classes, making verb forms more varied and intricate. For linguists, Icelandic offers a fascinating glimpse into the evolution of Germanic languages and the persistence of ancient grammatical structures.

6. Cree

Cree, spoken by the Cree people across Canada, is a polysynthetic language that presents a fascinating challenge with its complex verb morphology. In Cree, verbs can include multiple affixes that convey detailed information about the subject, object, tense, mood, and aspect, all within a single word.

For example:

- English (SVO): “The man (S) is eating (V) fish (O).”

- Cree: “Nipâwâw (he is eating).”

In Cree, the verb “nipâwâw” embodies the subject and the action in one word. This intricate verb conjugation system allows for a high degree of nuance and specificity but requires learners to master a variety of affixes and their combinations.

Additionally, Cree’s use of preverbs and postverbs to modify the main verb adds another layer of complexity, making sentence construction a detailed and precise process. For linguists, Cree is an intriguing subject of study due to its polysynthetic nature and the insights it offers into the cognitive processes involved in language formation and use.

7. Quechua

Quechua, the language of the Inca Empire, is still spoken by millions in the Andes today. It’s an agglutinative language, meaning it forms words by stringing together suffixes that each add specific meaning. This makes Quechua grammar both fascinating and complex.

For example:

- English (SVO): “I will go to the market.”

- Quechua: “Rantikuykipi purinqayku.” (We will go to the market.)

In Quechua, the verb “purinqayku” is formed by adding suffixes to the root verb “puri-” (to go), indicating future tense and inclusive “we”. The language’s extensive use of suffixes allows for precise and nuanced expression but requires learners to memorize and understand various affixes.

Quechua’s sentence structure typically follows a Subject-Object-Verb (SOV) order, differing from the common SVO order in English. This, combined with its agglutinative nature, offers linguists a rich field of study into how languages can encode meaning and structure thoughts.

8. Greenlandic

Greenlandic, an Inuit language spoken in Greenland, is a polysynthetic language known for its extraordinarily long words. In Greenlandic, words are formed by adding multiple affixes to a base word, creating what can be entire sentences in other languages.

For example:

- English (SVO): “The hunter (S) killed (V) the seal (O).”

- Greenlandic: “Pisuttuarpunga.” (I am going to the hunter.)

A single word in Greenlandic can convey what would take several words or even a whole sentence in English. For instance, “qangatasuukkuvimmuuriaqalaaqtutit” means “you will go to the airport.” This polysynthetic structure allows for precise and compact expression, but it requires a deep understanding of numerous affixes and their proper combinations.

Greenlandic’s structure delights linguists, providing insights into how languages can pack complex information into single lexical items. Its unique approach to word formation challenges conventional grammar rules, making it a captivating language to study and learn.

9. Hungarian

Hungarian, spoken in Hungary, is renowned for its extensive case marking and vowel harmony, presenting unique challenges to language learners. Unlike English, which has only a few grammatical cases, Hungarian has 18, each modifying nouns to indicate their role in a sentence.

For example:

- English (SVO): “The cat (S) sits (V) on the table (O).”

- Hungarian: “A macska (NOM) ül (V) az asztalon (SUP).” (The cat sits on the table.)

Hungarian also employs vowel harmony, meaning that vowels within a word must harmonize according to frontness or backness, affecting how suffixes are attached. This intricate system of vowel harmony and extensive case marking makes Hungarian a captivating language for linguists, offering deep insights into the flexibility and complexity of human language.

10. Archi

Archi, spoken by a small community in the Caucasus region of Russia, is a linguistic marvel due to its extreme phonological complexity and highly inflected verb system. Archi features a wide range of consonant and vowel sounds, creating a diverse set of phonetic possibilities, unlike English.

For example:

- English (SVO): “The boy (S) sees (V) the dog (O).”

- Archi: “Zikʷi (NOM) χʷīna (V) buch’u (ERG).” (The boy sees the dog.)

Archi verbs can have hundreds of forms depending on grammatical factors, including tense, aspect, mood, and agreement with the subject and object. This inflection level requires speakers to be adept at managing a multitude of verb endings and forms.

For linguists, Archi is particularly intriguing due to its rarity and the insight it provides into the limits of human language complexity. Learning Archi involves navigating a labyrinth of phonetic and morphological rules, making it a challenging yet rewarding experience for language enthusiasts.

Hey fellow Linguaholics! It’s me, Marcel. I am the proud owner of linguaholic.com. Languages have always been my passion and I have studied Linguistics, Computational Linguistics and Sinology at the University of Zurich. It is my utmost pleasure to share with all of you guys what I know about languages and linguistics in general.