Let’s talk meme.

Not the cat with laser eyes or the confused guy looking at butterflies (though, yes, we’ll get there). We’re going way back for this one—to evolutionary biology, Greek roots, and an Oxford biologist with a thing for replicating ideas.

Before it became a pixelated symbol of internet chaos, the word meme had a much nerdier—and surprisingly serious—origin story.

What is the meaning of meme?

A “meme” is an idea, behavior, or style that spreads from person to person within a culture—sort of like a gene, but for the brain. These days, it usually refers to funny images with text shared online.

Yeah, we’ve come a long way from the original.

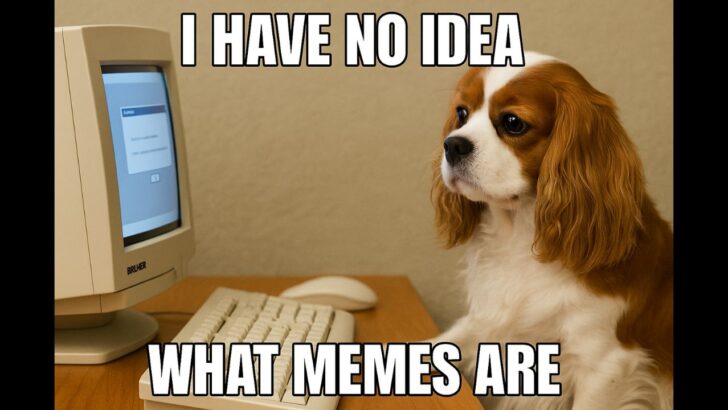

The current meaning of meme is probably familiar to anyone who’s touched the internet in the last 20 years: a captioned photo, a video clip, a TikTok sound, or some remixable template used to comment on everything from climate change to whether pineapple belongs on pizza.

But back in the 1970s, meme didn’t mean any of that.

It wasn’t a joke. It was a theory.

Origins: Not from Reddit, but from Richard Dawkins

The term meme was coined in 1976 by Richard Dawkins, a British evolutionary biologist best known for writing The Selfish Gene—a book that popularized the idea of seeing natural selection through the lens of competition between genes.

In one chapter, Dawkins wondered if there was an equivalent of the gene in the cultural world.

He thought: hey, genes replicate and evolve. What if ideas do too?

So, he came up with a word to describe this unit of cultural transmission. He wanted it to sound a bit like gene for symmetry, and he also wanted it to have roots in existing language.

Enter: meme.

From the Ancient Greek word mimema (μίμημα), meaning “that which is imitated,” Dawkins shortened it to make it catchy. He even says so in the book: “I want a monosyllable that sounds a bit like ‘gene.’”

Boom—meme was born.

So what exactly was a “meme” in 1976?

In its original context, a meme was anything that spreads through imitation—ideas, melodies, phrases, fashion trends, even religious beliefs.

Think of:

- The tune of “Happy Birthday”

- Catchphrases like “yada yada yada”

- Wearing your hat backwards because your favorite baseball player did

According to Dawkins, all of these count as memes. They replicate, mutate, and get passed along—not through DNA, but through language, behavior, and culture.

In other words, memes are contagious. And culture is one big petri dish.

And just like genes, memes compete for survival. The catchy ones live. The boring ones die.

The Internet Hijacks the Meme

Here’s where things take a turn. A few decades later, the internet happened.

And when internet culture met the idea of meme-as-replicating-idea, things got out of hand real quick.

Suddenly, meme meant something a lot more specific:

A funny image with bold white text that your cousin shared on Facebook three years after it stopped being funny.

It meant dancing baby GIFs in the late ‘90s, Rage Comics in the early 2010s, and today, it means TikTok trends, Instagram formats, and that one guy blinking in disbelief.

These memes still follow the original definition:

They’re shared, replicated, tweaked, and they evolve depending on what survives the cruel ecosystem of group chats and algorithmic feeds.

But they’ve also become something else.

They’re a kind of visual shorthand. A form of inside joke.

They’re how the internet talks to itself.

Memes as Language, Power, and Chaos

Internet memes are more than just jokes.

They’re tools—used to communicate, rally, critique, and yes, sometimes confuse everyone over 45.

They’ve been used to:

- Fuel political movements

- Satirize public figures

- Turn a brand into a laughingstock overnight

- Create massive shared moments of cultural absurdity (see: the Bernie Sanders mittens)

And while some people still see memes as lightweight or silly, it’s worth remembering: so were comic strips, political cartoons, and graffiti once upon a time.

If you want to see the cultural pulse of the moment, you check the memes.

Memes and Mutation: A Linguistic Perspective

One of the wildest things about memes is how fast they evolve.

In linguistics, words can take decades or centuries to shift meaning. Meme did it in under 30 years.

Online culture chewed up and spat out Dawkins’ theoretical framework, and now we have a word that means “a humorous internet image” to most people—ironically, the thing Dawkins didn’t even predict.

It’s a perfect example of what linguists call “semantic drift.”

And it’s kind of beautiful.

Language isn’t just a fixed set of definitions. It’s alive, messy, and constantly mutating.

So when you say “this is a meme,” you’re echoing a chain of imitations that stretches back to ancient Greece, through a British biologist, and into the brain of the person who captioned a stock photo of a distracted boyfriend.

Final Thoughts: The Meme as a Mirror

So what’s a meme?

It’s a little piece of culture that spreads.

Sometimes that culture is Plato.

Sometimes it’s Pepe the Frog.

Sometimes it’s a powerful protest slogan, and sometimes it’s just a frog sipping tea.

But what all memes have in common is this:

They get inside our heads.

They make us laugh, think, argue, share.

And then they mutate and do it all again.

When you see a meme and think, “This is dumb,” just remember:

You’re participating in one of the most uniquely human traditions we’ve ever invented.

We imitate.

We remix.

We meme.

And then we meme some more.

Hey fellow Linguaholics! It’s me, Marcel. I am the proud owner of linguaholic.com. Languages have always been my passion and I have studied Linguistics, Computational Linguistics and Sinology at the University of Zurich. It is my utmost pleasure to share with all of you guys what I know about languages and linguistics in general.